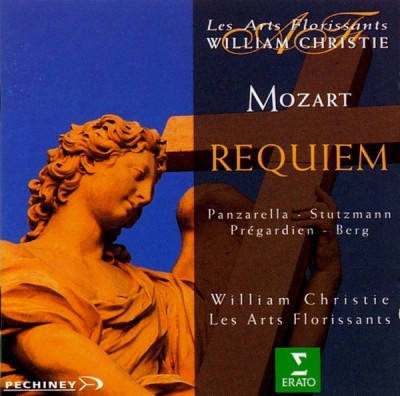

Alto: Nathalie Stutzmann

Tenor: Christoph Prégardien

Bass: Nathan Berg

Choir: Les Arts Florissants

Orchestra: Les Arts Florissants

Conductor: William Christie

Date: November 22-24, 1994

Venue: Salle Berthier, Paris, France

Cat No.: 0630-10697-2

Released: October 03, 1995

Both are played on period instruments, but there the resemblance ends: these two versions of the Mozart Requiem could scarcely be more unlike. It’s almost as if they are two different works. Well, to some extent, they are: William Christie gives the traditional Stissmayr text, with minimal emendation, while Pearlman records the recent Robert Levin revision, less sweeping than Richard Maunder’s but including a quite substantial “Amen” fugue (of his own composition, on Mozart’s subject) to end the Sequence and radically reworked versions of the “Osanna” fugue as well as much detailed rewriting to round off Siissmayr’s rough corners. But I was referring above less to the differences in the text than to those in approach.

The Boston performance is a faithful and careful reading of the work, direct and unaffected in style. It gives a very clear and sympathetic account of the Levin revision. The soloists are admirable, the men perhaps in particular — there is a sterling account of the “Tuba mirum” from the bass and some firm and tasteful singing from the tenor. The choir is accomplished though I did not greatly relish its actual sound as it comes over here: it seems a shade homogenized and characterless. The women’s voices in the upper parts — it continues to amaze me that ‘authentic’ performers who determinedly use period instruments are so ready to forego the authentic and quite different timbre of boys’ voices — are decidedly lacking in edge. But technically they are beyond reproach. The accuracy of the Kyrie fugue, at quite a lively pace, and the momentum of the “Dies irae”, attest the merits of the choir and their director. Tempos are sensibly judged, though I did think the “Recordare” a shade speedy, and that makes its counterpoint sound too busy. So this is a version to respect, a clear exposition of the Requiem, but ultimately a shade bland as a performance. It is on a fairly modest scale: strings are 6.4.3.3.2, the choir 6.5.5.5.

The Arts Florissants version is quite another matter, on a larger scale in every sense. The strings are 9.7.7.7.4. the choir 11.6.7.8. The emotions are bigger too. It is at once clear that this is to be a substantial, dramatic reading: the tempo for the “Requiem aeternam” is slow, but malleable, and Christie is ready to make the most of the changes in orchestral colour or choral texture, to mould the dynamics more than the (very sparse) original indicates, and indeed to dramatize the music to the utmost. Clearly he has little truck with any notion that this is an austere piece: he sees it as operatic, almost romantic — and the result is very compelling. There are points to which one might take exception, including some of the tempo variations, especially those that might seem to sentimentalize (the slow “Salve me” in the “Rex tremendae”, for example), and there are other surprising things: “Quantus tremor”, in a very weighty account of the “Dies irae”, for example, is hushed rather than terrifying; the “Recordare” is slow to the point of stickiness; there are rather mannered crescendos in the Sanctus: and often cadences are drawn out, for example in the “11 ostias”.

The powerful choruses of the Sequence are imposingly done, and the grave “Lacrimosa” wonderfully catches the special significance not only of the music itself but also of the fact that this is the moment where Mozart’s last autograph trails off. The choral singing is sharp-etched and generally distinguished: the choir give a vigorous yet finely dovetailed “Kyrie” fugue and the “Quarn ohm Abrahae” is splendidly sturdy. The soprano’s melting tone is sometimes very appealing, and Pregardien is an excellent stylist, but the solo singing is not generally outstanding, yet the Beneclictus is particularly impressive, very shapely and refined, In short, this is a reading full of character and ideas, very much a conscious modern interpretation of the work and very finely executed. It is followed by perhaps the only piece that the Requiem can reasonably be followed by, the Ave rerunn corpus, in a slow, hushed, rather romantic reading that is undeniably moving.

— Stanley Sadie, Gramophone [11/1995]