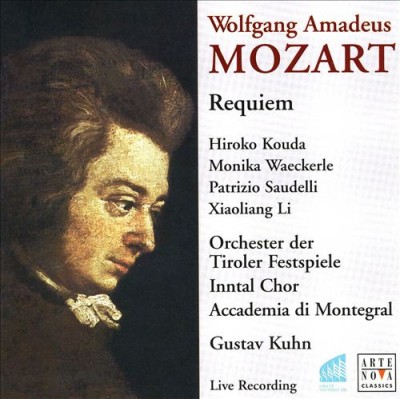

Mezzo-Soprano: Monika Waeckerle

Tenor: Patrizio Saudelli

Bass: Xiaoliang Li

Choir: Inntal Chorus, Montegral Academy Singers, Erl Choral Society

Orchestra: Tirol Festival Orchestra

Conductor: Gustav Kuhn

Date: July 22, 2001

Venue: Tiroler Festspiele, Erl, Austria

Live Recording

Cat No.: 74321 87073-2

Released: 2001

— George Hall, BBC Music Magazine [January 20, 2012] Kuhn’s capable Requiem pales beside Spering’s fascinating‚ sometimes eccentric but better performed investigations

The Requiem from Gustav Kuhn has most of the usual advantages and disadvantages of a recorded public performance. It has the sense of a live communication‚ singers to audience – and many of the choral numbers especially are vividly done‚ for example the forceful ‘Dies irae’‚ the particularly moving ‘Lacrimosa’‚ the solemn and reflective ‘Agnus Dei’. Kuhn draws strong singing even if the recording of the choir is less than ideally clear; textures in the denser movements‚ such as the ‘Hostias’‚ tend to be blurry. The solo singing is a little ordinary; the soprano‚ slightly effortful‚ does not find a lot of poetry in the music‚ although her solos in the closing items are persuasive. The bass is either too small in voice or is rather distantly recorded. The ‘Benedictus’ seems to me overintense for what is usually an oasis of calm. Kuhn directs with no eccentricities; this is in sum a capable performance with many good things but no special insights.

Christoph Spering’s is quite another matter. Informed by some (highly questionable) theories about the significance of Mozart’s tempo directions‚ and his realisation (which may not be unique to him) that the Requiem‚ as the Catholic church’s central collection of texts for the burial service‚ should not be performed ‘in a casual‚ even bouncy way’‚ he goes to the opposite extreme and takes the opening movements extraordinarily slowly. The effect is‚ of course‚ grave and imposing‚ and the ‘Kyrie’ fugue is powerful when done with such deliberation‚ even if it doesn’t make musical good sense. But when this music recurs at the end of the work he takes it considerably quicker‚ partly on theological grounds‚ partly because there is no tempo indication in the original. This is at best a shaky argument. Süssmayr is likely to have omitted the tempo marking because it was unnecessary: ‘Tempo I’ is implicit‚ and any departure would certainly have had to be made explicit.

Nevertheless‚ there are some striking things in this performance. Note‚ for example‚ the precision and clarity of the choral articulation in the ‘Dies irae’ and the textures in the ‘Rex tremendae’‚ the strong contrasts in the ‘Confutatis’ and its beautifully judged soft ending‚ the pleasantly flowing ‘Domine Jesu’‚ or the outstandingly expressive and shapely ‘Benedictus’. The trombones supporting the choir are brought out with more than usual clarity. The ‘Recordare’ is taken very slowly‚ to an extent that it imposes some strain on the singers. The soprano’s vibrato is marked here‚ but she is impressive even if some of the notes seem to be attacked from below. There is an excellent contralto‚ a smooth and even tenor‚ and a bass of some depth.

As a kind of supplement‚ Mozart’s original material for the eight movements of which autograph versions survive is played‚ just as it stands. Some may find this revealing‚ in that it serves to remind you how much Süssmayr and others had to add. But its meaning‚ as actual music‚ is limited: Mozart’s standard method of composing (to oversimplify a little) was to draft each movement‚ showing the essential lines and the movement’s total shape‚ and then to go back and fill in the details of harmony‚ orchestration etc. Most of these eight movements represent that sort of ‘continuity sketch’. As music to be heard‚ it has no artistic significance. Listeners should remember too that there almost certainly once existed a good deal more material by Mozart‚ probably drawn upon by Süssmayr in some of the other movements.

Still‚ this is an interesting issue‚ and I am glad to have heard Spering’s reading of the work‚ eccentric though it is.

— Gramophone [May 2002]