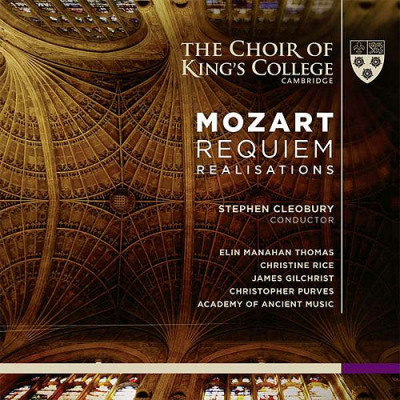

Mezzo-Soprano: Christine Rice

Tenor: James Gilchrist

Bass-Baritone: Christopher Purves

Choir: King’s College Choir

Orchestra: Academy of Ancient Music

Conductor: Stephen Cleobury

Date: June & September 2011

Venue: Chapel of King’s College, Cambridge

Cat No.: KGS0002

Released: 2013

The second disc presents a 68-minute audio documentary on the musical roots of the Requiem written by the renowned Mozart scholar Cliff Eisen, featuring musical examples from the requiem and the works from which it draws inspiration, highlighting striking similarities between Mozart’s work and that of several contemporaries and predecessors.

The Choir, conducted by its Director of Music, Stephen Cleobury, is joined for the recording by the Academy of Ancient Music playing period instruments. The soloists are Elin Manahan Thomas, Christine Rice and former King’s College choral scholars, James Gilchrist and Christopher Purves.

For all the talk about preferred editions from musicologists, critics, and the musicians themselves, no one will dispute that nearly every edition has some serious issues in scoring and texture. Some prefer Franz Beyer’s take, accepted by musicians as dissimilar as Leonard Bernstein and Nikolaus Harnoncourt. Others prefer the innovations of noted scholar and keyboardist Robert D. Levin. I myself have performed the Levin, and it is usually this version that I return to, in addition to the Beyer. Still others accept the Süssmayr as truth. So it is a great favor to all of us to have a program such as this, one which gives the “familiar” Süssmayr reading and then adds several re-scored movements. Along with the audio documentary on disc two – which like all documentaries will either bore or fascinate – the whole project seeks to explore our understanding of a work that is both remarkable and flawed.

Absolutely none of the above would matter if the readings here were not musically excellent, but happily the artistic qualities match the intellectual intentions. Stephen Cleobury leads an utterly flowing, natural, and un-heavy performance of a reconstruction that tends to bog down under its own weight; religiously, musically, you name it. The choir is naturally nothing short of fabulous, fully aiding this approach. The result is a convincing look at the Süssmayr, a major achievement in my book. I don’t mean to imply that any of the solemnity and grandeur is lost, it is still very tangible. But with outstanding support from the Academy of Ancient Music, Cleobury’s take on the score is an exceptional way to play this music. The soloists are just fine; I have never recommended this work on the soloists alone, and this album isn’t changing that. I will say that they respond with commitment to the vision on the podium, and they are an asset, if that matters to you.

As for the fragments, they are equally well-played and sung, and enhance the value of this issue considerably. The Amen fugue is here arranged by one C. Richard F. Maunder; it appears somewhat differently in the Levin completion as well. The Sanctus is equally Levin’s and Beyer’s, and the former openly admits that in his edition of the score, so all is well there. The final three arrangements aren’t especially earth-shattering, but they too hold surprises and will be welcome to anyone who loves this music. Throughout the entire project, the sound is terrific. A must for… well, everyone.

— Brian Wigman, Classical Net [2014]