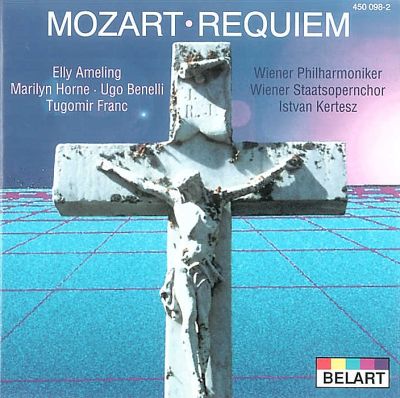

Mezzo-Soprano: Marilyn Horne

Tenor: Ugo Benelli

Bass: Tugomir Franc

Choir: Wiener Staatsopernchor

Orchestra: Wiener Philharmoniker

Conductor: István Kertész

Date: October 1965

Venue: Sofiensaal, Vienna, Austria

Cat No.: 450 098-2

Released: 1994

— Victor Carr Jr, Classics Today [2001] This is big, old-fashioned Mozart, and is all the better for it.

Don’t expect any period inflections or early-music-subtleties from these 1960s performances from Kertész: instead revel in the big, lush sounds and sumptuous textures. The performers in the Requiem are the peerless Vienna Philharmonic who play with all the grace and grandeur one would expect from one of Europe’s finest orchestras. The close-up recording allows you to “wallow” in their sound in a way that is largely impossible with performances from smaller-scale period bands. Kertész himself has a noticeably old-school approach to the Requiem: the Rex Tremendae, for example, is taken far more slowly than you would expect to hear in most performances today. However, he is surprisingly fleet of foot in the opening Introitus and he keeps the fugue in the Offertorio going at quite a lick before expanding to revel in the rit. at the end.

The solo singing is almost uniformly excellent. Elly Ameling has a wonderful purity of tone that shines through all of her big moments, reminding me of the young Gundula Janowitz. The under-recorded Ugo Beneli is an Italian tenor of the old school who wears his heart on his sleeve, and Marilyn Horne is astonishingly characterful in her singing. Her rich Rossini heritage is obvious here and her contribution to the Tuba Mirum in particular makes one sit up and take notice. Only Tugomir Franc is a bit underwhelming: his opening phrase of the Tuba Mirum is gravelly and lacks the consistency of tone that is so obvious in his colleagues. He is particularly under-parted during the Recordare which he begins by tending to blend into the background and let the others do the work, though he improves by the beginning of the Ingemisco. The Vienna State Opera Chorus are very obviously an opera chorus: you would never think that this is a liturgical choir! That does mean that you miss out on some of the devotional aspects of this work and at times they are rather rough around the edges, but they make up for it with a – sometimes startling – grasp of the drama behind this work. If you don’t mind being grabbed and compelled through the choruses then you will love this. Just listen to the Confutatis to see what I mean!

The sound on this recording is both a blessing and a curse. Engineered by Erik Smith and Gordon Parry, part of the legendary team behind the Decca Ring Cycle, every single aspect of the music is captured with clarity that is breathtaking for the time. Decca has always prided itself on the quality of its opera sound and those skills transfer ideally to this recording, at least in terms of the voices. You can hear, for example, different sections of the choir coming in through different channels – basses to the left, tenors to the right – and this helps to catch you up in the music in a way that a perfectly blended performance perhaps misses. The snag is that at times you can hear individual singers dominating over their section and that at times, particularly in the Dies Irae, the orchestra is noticeably in the background. On the other hand, the trombone solo at the beginning of the Tuba Mirum is quite appropriately spotlit. Personally, though, I love the sense this whole recording gives of being part of a performance, and it illuminated textures in the work which I hadn’t picked up on before.

— Simon Thompson, MusicWeb International [June 2008]