Mezzo-Soprano: Rowan Hellier

Tenor: Thomas Hobbs

Bass: Matthew Brook

Choir: Dunedin Consort

Orchestra: Dunedin Consort

Conductor: John Butt

Date: September 15-19, 2013

Venue: Greyfriar’s Kirk, Edinburgh, UK

Cat No.: CKD 449

Released: March 25, 2014

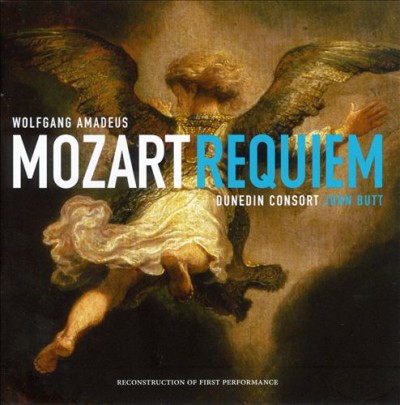

Mozart’s Requiem – Reconstruction of First Performances

As a scholar once quipped in relation to Mozart’s final work: ‘Requiem, but no Piece’. Mozart’s Requiem has been a site for controversy since almost the time of the composer’s untimely death, and it is clear that it is never going to be complete, at least as a piece by Mozart. On the other hand, it is perhaps testimony to the quality of what does survive that musicians and scholars have given it such persistent attention. While some of its popularity can be attributed to romantic notions of the dying genius doing his utmost to crown his life’s work in the most sublime fashion, there is no doubt that the vast proportion of the surviving material is remarkable in its musical cohesion and emotional power.

In the early nineteenth century, the controversy was over how much of the Requiem was really the work of Mozart and how much of it was completed by Franz Xaver Süssmayr. By the turn of our current century, the extent of Süssmayr’s involvement had been clearly established – so far as is likely to be possible – and the discussion moved towards the question of whether modern scholars could provide a completion superior to Süssmayr’s. Now that there are a number of ‘new’ versions of the Requiem, perhaps performing the ‘original’ completion is almost as controversial as performing a modern version

If Süssmayr’s completion does contain obvious weaknesses in terms of certain movements (most obviously the ‘Sanctus’ and ‘Osanna’), and of various details of part-writing and orchestration, Süssmayr remains the only figure in this who actually knew Mozart and shared essential elements of his musical culture. Moreover, it was Süssmayr’s version that was known as ‘the’ Mozart Requiem for countless musicians and listeners until the last decades of the twentieth century. It provided material that finds echoes in several major composers (Verdi, Bruckner and Fauré immediately come to mind), so it would surely be wrong to discount a large period of productive reception on the pretext that inspired listeners were hearing partly in error.

The recent publication of David Black’s new edition of Süssmayr’s version provides an excellent opportunity to record the original completion yet again. Not only does the new edition show very clearly the areas completed by Mozart and the precise extent of Süssmayr’s additions, it also presents several details that have been obscured by later ‘improvements’, particularly those added in the first published edition (which does not mention Süssmayr), by Breitkopf & Härtel in 1800. Black’s new edition therefore returns the work to the state it was in during the first, crucial years of its exposure to the public, and this in turn provides an ideal opportunity to consider how the work may actually have sounded at its very first performance.

It would be natural to assume that the first performance of the Requiem was the one arranged by the original commissioner (and purported composer), Franz Count von Walsegg, at a Mass in memory of his wife at a church in Wiener Neustadt on 14 December 1793. But in fact (and probably without the count’s knowledge), Süssmayr’s completion of the Requiem had already been presented in Vienna on 2 January 1793, just over a year after the composer’s death. This was at a well-documented benefit concert for Mozart’s widow, Constanze, which his great friend and patron, Baron Gottfried van Swieten, promoted at a hall connected to a prestigious restaurant. Van Swieten was closely associated with Mozart’s assimilation of several key works by Bach and Handel during his Viennese years, but he was also responsible for encouraging the composer to arrange several such works, primarily by Handel, for performance with the Gesellschaft der Associierten Cavaliere in 1788-90. This society was reconvened for the benefit concert of 1793, so – although we do not have any details of the forces for this specific performance – Mozart’s Handel performances of just a few years previously offer a fairly consistent picture of the type and size of the performing group involved. Among other details, the most striking in terms of choral practice today is the fact that the chorus of c.16 singers is led by the four soloists rather than corralled as a separate body of performers. This not only helps to integrate the solo sections with the choral ones (there are several swift changes from one texture to the other, both across movements and sometimes within them); it also gives the choral line a different character, one inflected by soloistic projection. This method of performance was entirely standard in much European choral music of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries (and is well demonstrated in all Dunedin performances of works by Bach and Handel), and Mozart’s practice was no different in this respect.

If the two main challenges of this project are to explore the implications of Mozart’s likely choral texture, and to try and envisage how the work may have been heard for the very first time, both are made more problematic by the strong possibility that there was an earlier performance of at least part of the Requiem. The fact that there was a Requiem Mass held for Mozart in St Michael’s Church on 10 December 1791 (five days after his death) has been well established, but two of the four references to this note that Mozart’s ‘own Requiem’ was performed. While there is an outside chance that all the sketched movements (most of the sequence and the offertory) may have been performed with just the composed vocal parts and a realized organ accompaniment, the most likely sections to have been performed would be the opening introit (entirely finished by Mozart) and the ‘Kyrie’, which was orchestrated with colla parte instruments by two unknown hands shortly after Mozart’s death. We have a relatively clear idea of the forces available at the church: about half the number of strings used in the 1793 premiere and a standard vocal complement of eight singers. Again, the singers would most likely have comprised four of solo capability and four (or slightly more) doubling ripienists, so the basic choral principle would have been the same. Given that there is evidence of at least one other performance with a choir of this small scale during the early years of the work’s existence, there is every incentive to imagine what a small-forces version might have sounded like.

The library of St Michael’s Church also contains parts for Mozart’s early offertory Misericordias Domini, K. 222, recently identified by David Black. These date from around 1791 (there are records to show that a motet by Mozart was copied in May that year) and therefore imply a performance at the church during the last year of Mozart’s life, with the same scale of forces as was to be used in the Requiem service. This piece furthermore provides a very interesting companion to the Requiem, given that it is in the same key and is an essay in contrapuntal construction. The short text (‘I will sing of the mercies of the Lord for ever’) spawns a piece of almost comical length: not only is virtually every contrapuntal combination of the opening material explored in turn, but Mozart in ‘neo-modal’ style visits virtually every key centre of the scale (except the awkward phrygian mode of the second degree). This systematic approach to composition is balanced by an overall form that uses sonata principles (the ‘second subject’ is uncannily similar to the opening of Beethoven’s ‘Ode to Joy’) and a dramatized conclusion. At the very least, this fascinating piece gives us an idea of some of the compositional challenges that Mozart relished, particularly those that he would tackle to such effect in his very last work.

Mozart would probably have balked at his swift canonisation and found the issues of the Requiem’s authorship rather amusing: composition to him was normally a spontaneous affair, somewhat akin to performance, and impersonation was one of his own specifically musical gifts. Yet through this mercurial, frenetic approach to his profession, Mozart achieved a profundity that is truly startling. Within the necessary sobriety of a church idiom he was able to pack in virtually all the styles and textures he had developed on the opera and concert stage, bringing a dramatic flair to the Requiem text that has been a challenge to all subsequent composers in the genre. The opening movement sees him taking the traditional elements of church music – plainsong cantus firmus and fugue – and imbuing them with a lyricism and momentum that would normally be associated with much more up-to-date genres of music. Mozart’s debt to the opening chorus of Handel’s funeral anthem The ways of Zion do mourn (which may well have also played a part in the invention of the ‘Song of the Armed Men’ from Die Zauberflöte, written at very nearly the same time) seems almost certain. But the transformation is clearly Mozart’s own, rendering this opening, with its very human, almost limping gait, one of the most recognizable in western music. It would be easy to imagine that such a combination of ‘modern’ human elements and traditional church style might render the latter as a sort of parody, but somehow both styles are integrated without either necessarily sounding like the ‘home’ style.

Mozart’s late contrapuntal style is also evident in the ‘Kyrie’ (again borrowing from Handel, this time from the end of the Dettingen anthem) and ‘Quam olim Abrahae’ fugues, ones in which we can almost hear the composer’s imaginary competition with Bach, as he discovers and deploys as many combinations as possible. Perhaps it is this sense of historical competition that gives these pieces such dramatic energy, a sort of desperation that is a model for anguished music in the classical era. Another particular challenge must have been the sequence, with its long, rambling text. Rather like a keyboard fantasia in its variety of stylistic allusions, Mozart’s sequence takes us swiftly from dramatic fantasy, through operatic ensemble, French overture, ritornello vocal ‘concerto’ , back to fantasy and closing lament (a surviving sketch by Mozart suggests that an Amen fugue may originally have been planned). The musical sequence thus provides a sort of roundedness that the text here tends to lack. Only the ‘Tuba mirum’ is in a completely open form, ending with no reference to its opening melody, as if it were following the swift psychological progress of an operatic ensemble.

Aspects of sonata style are also a means of providing contrast within cohesion: in the very first movement the ‘Te decet hymnus’ section, set to the Gregorian tonus peregrinus, provides a contrasting ‘second subject’. Yet the circling figuration of the instrumental parts at this point is later integrated into a countersubject for the return of the ‘Requiem’ theme. Of the various vocal idioms that Mozart had at his disposal, only aria is effectively absent. But aspects of aria style are readily evident in fully choral numbers such as the ‘Lacrimosa’ and ‘Hostias’ , and also in the largely convincing ‘Benedictus’ ensemble, for which there is sadly no evidence of Mozart’s direct compositional involvement. In all, absolute originality of musical material is clearly not the essential aspect of Mozart’s achievement. Rather it is his stunning ability to combine the diverse idioms and genres of varying ages, in such a way as to generate works that seem ever new and direct. And such directness almost always seems to bring with it the trace of human emotions and movement, as if Mozart could capture the physical and mental essence of people in a way that we can almost recognize.

Performance Issues

Mozart’s own Requiem Mass in St Michael’s Church on 10 December 1791 seems to have been organized partly by the impresario, librettist and actor (and thus Mozart’s close collaborator in Die Zauberflöte), Emanuel Schikaneder. The church was specifically associated with the court, its musicians and the operatic community. Both the available lists of

musicians and the parts for the Misericordias point to an ensemble of eight singers, single wind and single lower strings with doubled violins. It may well be that the opera musicians came up with instruments that were not normally available, specifically the two basset horns. The doubling of vocal lines in contrapuntal music by trombones was standard practice, evident in the Misericordias parts, and is particularly effective when there are only two singers per part. While it is likely that trumpets and timpani would have been available for Mozart’s fully finished introit, it is not clear whether the parts for these instruments in the ‘Kyrie’ were written before 10 December 1791, so they are omitted in the small, ‘church’ version of the ‘Kyrie’.

For the 1793 performance of the completed Requiem, the surviving parts of several of Mozart’s Handel performances give us a reasonable indication of the numbers involved. These performances had also been promoted by van Swieten with the same society and, indeed, Mozart’s version of Acis and Galatea was performed in the same venue as the Requiem, the Jahn-Saal in Vienna. The vocal forces therefore comprise the four soloists plus up to three ripienists and the strings are provided with a relatively generous six violins to a part, with slightly smaller numbers for the lower parts. The sorts of soloist available in the Handel performances were very clearly associated with dramatic performance (for instance, Mozart’s sister-in-law, Aloysia Weber, was a regular member of the ensemble), which might suggest that the choruses benefited from a relatively soloistic form of delivery. One particular issue about the venue was the fact that no organ was available in the hall. While the role of a keyboard continuo is less vital here than in earlier church styles, it is unlikely that it would have been missed out entirely. The 1793 performance may well thus have employed a fortepiano for the purpose (a reference survives for the use of a fortepiano in a performance of the Requiem in Stockholm, some ten years later).

This project would not have been possible without the wonderful support of Dr David Black, who gave me early access to his new edition of the Süssmayr version of the Requiem and also to his seminal dissertation on the church-music culture of Mozart’s Vienna. He has pointed me in the right direction in numerous ways, particularly in relation to the sources for the size and type of forces. Thanks are also due to David Lee for preparing the performing edition of the Misericordias from the original St Michael’s Church parts.

© John Butt, 2014

As with all of Butt’s recordings, however, this Mozart Requiem is something of an event. The occasion is the publication of a new edition – by David Black, a senior research fellow at Homerton College, Cambridge – of the ‘traditional’ completion of this tantalisingly unfinished work, of which this is the first recording. Süssmayr’s much-maligned filling-in of the Requiem torso has lately enjoyed a resurgence in its acceptance by the scholarly community – not that it has ever been supplanted in the hearts and repertoires of choral societies and music lovers around the world. The vogue for stripped-back and reimagined modern completions is on the wane and Süssmayr’s attempt, for all its perceived inconsistencies and inaccuracies, is once again in favour in the crucible of musicological criticism. After all, as Black points out in the preface to his score, ‘Whatever the shortcomings of Süssmayr’s completion, it is the only document that may transmit otherwise lost directions or written material from Mozart’.

Black has returned to the earliest sources of the work: Mozart’s incomplete ‘working’ score, Süssmayr’s ‘delivery’ score and the first printed edition of 1800, which even so soon after the work’s genesis was already manifesting accretions and errors that place us at a further remove from Mozart’s intentions. For all the textual emendations this engenders, the actual difference as far as the general listener is concerned is likely to be minimal; while we Requiemophiles quiver with delight at each clarified marking, to all intents and purposes what is presented here is the Mozart Requiem as it has been known and loved for more than two centuries.

It is Butt’s minute attention to these details, though, that makes this such a thrilling performance. He fields a choir and band of dimensions similar to the forces at the first performance of the complete work on January 2, 1793, little over a year after Mozart’s death, and the effect is, not unexpectedly, to wipe away the impression of a ‘thick, grey crust’ that was felt so palpably by earlier commentators on the work. Listen, for example, to Mozart’s miraculous counterpoint at ‘Te decet hymnus’ in the Introit or Süssmayr’s rather more clumsy imitation in the ‘Recordare’, and hear how refreshingly the air circulates around these potentially stifling textures.Butt’s outlook on the work is apparent from the very beginning: the gait of the string quavers is more deliberate than limping in the first bar, and this purposefulness returns in movements such as the ‘Recordare’ and ‘Hostias’. The extremes of monumentality and meditativeness in the Requiem are represented perhaps by Bernstein and Herreweghe respectively; Butt steers a course equidistant between the two without compromising the work in its many moments of austerity or repose. Paradoxically, Butt’s fidelity to the minutiae of the score allows him the freedom to shape a performance of remarkable cumulative intensity, so that the drama initiated in the driving ‘Dies irae’ reaches a climax and catharsis in the ‘Lacrimosa’ and is recalled in the turbulent Agnus Dei.

The choir is of only 16 voices, from which the four soloists step out as required. Blend and tuning are of an accuracy all too rarely heard, even in this golden age of British choral singing. Soprano Joanne Lunn’s tone is well nourished, with vibrato deployed judiciously to colour selected notes or phrases; of the other soloists, Matthew Brook’s bass responds sonorously to the sounding of the last trumpet (in German ‘die letzte Posaune’ – the last trombone) in the ‘Tuba mirum’. Instrumental sonority, too, is meticulously judged: hear especially the voicing of the brass-and-wind chords during bridge passages in the ‘Benedictus’ or the shifting orchestral perspectives of the ‘Confutatis’.

The couplings are also carefully considered. The first is Misericordias Domini, an offertory composed in 1775 of which Mozart had a set of parts copied in 1791. Sharing with the Requiem its key and a gleeful exploitation of contrapuntal techniques, it piquantly demonstrates the advance in Mozart’s church style during the last 16 years of his life.

The disc closes with what purports to be a re-enactment of an even earlier ‘first performance’ of the Requiem. While the 1793 Vienna concert is well documented, recent research has suggested that the Requiem (or at least some of it) was performed in a memorial to Mozart on December 10, 1791 – only five days after his death. Given the partial state of the work (only the Introit was complete in Mozart’s hand), it is supposed that this performance consisted of the Introit and the ensuing Kyrie fugue, for which an amanuensis filled in the doubling woodwind parts. That performance is hypothesised here with slimmed-down vocal and string parts, and with trumpets and drums missing from the Kyrie (on the presumption that the parts hadn’t been provided by that time). Starker still than the larger performance, this telling appendix offers a tantalising glimpse of the music that might have been played by Mozart’s friends and students as they struggled to come to terms with their loss.

— David Threasher, Gramophone [May 2014]

John Butt’s approach with the Dunedin Consort, though, is different. He maintains that whatever the weaknesses in Süssmayr’s work, he did at least know Mozart, and the version that he came up with proved hugely influential for the next two centuries.

The Dunedin version is described as a “reconstruction of the first performance” – in other words, an attempt to realise the score as Süssmayr completed it, and which was heard at the benefit concert for Mozart’s widow, Constanze, in Vienna in 1793. As Butt points out, however, there may have been an even earlier performance of the score that Mozart completed, at his own funeral in 1791, and a reconstruction of that performance, which would have consisted just of the Requiem Aeternam and the Kyrie, with the likely forces – eight singers, with single wind and lower strings but doubled violins – is also included on this disc.

The choir and orchestra used for the reconstruction of the 1793 complete performance is larger – a choir of 16, including soloists, and an orchestra of 30, including a fortepiano continuo. Butt’s account is as much an exploration of the sound world that the 1793 audience would have experienced as it is of the rights and wrongs of what Süssmayr did. Anyone used to a suave choral sound in performances of the Requiem might be surprised by the almost granular texture here, in which every voice makes its own distinctive contribution, and by the pungency with which the orchestral writing registers. There’s a real energy, with tremendous climaxes that belie the scale of the forces involved. It’s not going to be the last word on what will remain the unsolvable riddle of Mozart’s final masterpiece, but it’s a salutary corrective to some of the academic speculation.

— Andrew Clements, The Guardian [April 2, 2014]

— Blair Sanderson, AllMusic.com