Mezzo-Soprano: Christel Borchers

Tenor: Peter Straka

Bass: Matthias Hölle

Choir: Munich Philharmonic Choir

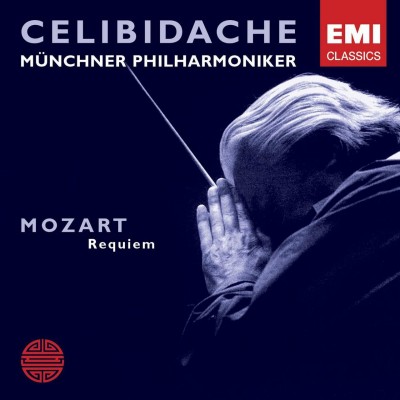

Orchestra: Münchner Philharmoniker

Conductor: Sergiu Celibidache

Date: February 15 & 17, 1995

Venue: Philharmonie im Gasteig, Munich, Germany

Live Recording

Cat No.: 7243 5 57847 2 8

Released: 2004

— Mike D. Brownell, AllMusic.com

This performance will be anathema to those who prefer to hear Mozart’s Requiem in so-called ‘authentic’ guise, that is with rapid tempos executed by a smallish choir accompanied by a ‘period’ band. If one were to describe Sergiu Celibidache’s interpretation as ‘romantic’, I do not mean by this that it is lush and self-indulgent; rather, his conception is on a big and expansive scale, with plenty of space for reflection on the portent of the text. This is, after all, a work of commemoration intended for solemn liturgical usage.

EMI has included applause before and after the performance, which will, of course, serve to remind listeners of the recording’s live provenance, but the clapping, fortunately, is separately tracked. The opening ‘Introitus’ is extraordinarily slow, creating a profoundly sombre atmosphere right from the first phrases, with the suspensions in bassoons and basset-horns sounding exceptionally poignant. Celibidache takes nearly eight minutes over this movement. The only remotely comparable performance of which I am aware is Leonard Bernstein’s for DG – also recorded live, in 1988, just over two years before his death – and yet he is about 90 seconds faster here. In terms of overall duration, Bernstein takes about 10 minutes less than Celibidache. Ironically, with a couple of notable exceptions, Celibidache’s reading (recorded just over a year before his own passing) never ‘feels’ laboured. It is reverential and reflective, but not at all lacking in drama at apposite moments.

The choir sings with weight and a full-bodied tone; just occasionally, perhaps taxed by the spacious tempos, the choir’s members are slightly under the note, but their sense of commitment and involvement in the (compiled) performance is both impressive and affecting.

The contrapuntal lines in the ‘Kyrie’ and ‘Domine Jesu’, in spite of the choir’s numbers, are unusually clear, undoubtedly aided by a basic pulse which allows notes to register clearly, rather than just moving swiftly on. In the ‘Dies Irae’, there is a powerful response from all forces to the text and its references to Judgement Day – the sense of awe and terror being most vividly projected – and the bright D major of the ‘Sanctus’ blazes forth in a rare moment of triumph and exultation. Incidentally, the choral “Osanna”s here and in the ‘Benedictus’ are notable for their conviction of execution. Celibidache ensures that the comparatively infrequent passages of major-key music in this otherwise largely dark minor-key-tinged score are moments of hope and consolation – the soloists-led ‘Recordare’ and ‘Benedictus’ being movements of solace amidst the general mood of grieving.

The soloists make a very fine team, both individually and as an ensemble. One often encounters performances where the individuals are fine, but that a cohesive blend is lacking or wanting. Here, Celibidache has moulded his singers into what is almost a concertante group, with solo lines prominent as and when needed, but then merging together without voices obtruding or vying for attention. The only passage where one feels a real lack of the momentum, which is implicit in the music, is the ‘Confutatis’, where the strings depict the ‘flames’ of the text with rapid figuration. One might be blunt and suggest that this movement is simply ‘too slow’, though the sotto voce pleas from sopranos and altos, and the ‘oro supplex’ setting, are rapt and prayerful.

Celibidache follows the ‘standard’ Süssmayr edition and like so many of Celibidache’s performances, this reading of Mozart’s Requiem is, literally, incomparable. Bernstein has a similar air of weighty tragedy, whilst Benjamin Britten’s conducting on BBC Legends has a comparable intensity, though he is fleeter-footed and has a greater sense of urgency. It is interesting to note that these three exceptionally interesting performances come from composer/conductors and originate from near the end of their respective lives – perhaps, unwittingly and retrospectively, contributing to the valedictory feeling they share.

For a uniquely considered view of Mozart’s unfinished masterpiece, and a profoundly emotional rendering, I would urge you to give Celibidache a hearing.

— Timothy Ball, ClassicalSource.com [May 31, 2005]