Mezzo-Soprano: Anne Buter

Tenor: Marcus Ullmann

Bass: Martin Snell

Choir: Gewandhaus Chamber Chorus

Orchestra: Leipzig Chamber Orchestra

Conductor: Morten Schuldt-Jensen

Date: November 10 – 12, 2004

Venue: Great Hall, Gewandhaus, Leipzig, Germany

Cat No.: 8.557728

Released: 2005

In truth, Haydn’s The Seasons is a neglected masterwork, and a performance as good as this one shows why. It was written in 1801, the same year as the first performance of Beethoven’s First Symphony, and it harks back to earlier times more clearly than does Haydn’s other great oratorio, The Creation – which he finished two years earlier. The earlier work’s timeless story and inherent drama helped carry it forth despite the passing of the age of grand-scale oratorio. But The Seasons has text that is at best mediocre (by Baron Gottfried van Swieten, after James Thomson and others), and its subject matter simply does not enthrall: rural simplicity through the seasons of the year. Unlike The Creation, this later oratorio creaks.

This does not mean it lacks wonderful music. Some sections are marvelous: much of Summer is an effective portrayal of heat and stillness, while the final two movements, representing a thunderstorm and the happiness after it is over, look forward to Beethoven’s Pastorale symphony of later in the decade; the Fall chorus, Hört des laute Getön, has hunting-horn raucousness exceeding that of Haydn’s “Hornsignal” symphony (No. 31); the final Fall chorus, Juhhe, juhhe! Der Wein ist da has all the drama and bounce of the “Military” symphony (No. 100), and equal sweep; the overture to Winter excels as a mysterious tone painting of fog, while that of Spring seems to make the entire year bloom. But the work as a whole is less effective than its component parts: two-and-a-quarter hours of planting, shady groves, harvests and frozen lakes is more than enough, however well the music is played and sung.

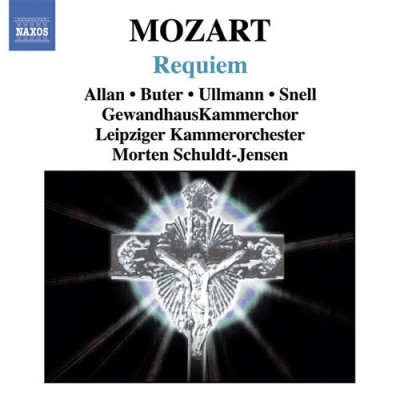

Mozart’s Requiem is less than enough: the composer’s final work, far from finished at his death, is in large part reflective of the reconstructive efforts of Franz Xaver Süssmayr. Kudos are due to Naxos for indicating in its booklet for this release just which parts are by Mozart, which are by Süssmayr, and which are a blend. The performance is quite well sung: almost operatic in parts, heartfelt in others, gentle in still others. Soprano Miriam Allan, whose bell-like voice makes her sound almost like a boy soprano, is especially effective. Schuldt-Jensen shapes the music respectfully and without undue heaviness – despite the subject matter, this is music more thoughtful than depressing. The inclusion of two Offertories set by Mozart earlier in his life is an unexpected joy: both are well-worked, brightly conceived, yet entirely reverential. Schuldt-Jensen’s argument for authentic performance practice using modern instruments is far more convincing when you hear how it works than it is when he presents his viewpoint in words.

Mark Estren, April 2006